National Museum of African American Music becomes a Nashville reality

hbeecherhicks

on

February 7, 2023

Hallowed Sound

‘Bring us back together’: H. Beecher Hicks III on opening the National Museum of African American Music

As the National Museum of African American Music opens its doors, journalists from the USA TODAY Network explore the stories, places and people who helped make music what it is today in our expansive series, Hallowed Sound.

After more than two decades, the National Museum of African American Music is bringing “One Nation Under a Groove.” The long-awaited museum officially opened its doors Jan. 18 in downtown Nashville.

Sitting across the street from the Ryman Auditorium and a string of famed honky-tonks, its 56,000-square-foot space offers something new to Lower Broadway: seven galleries dedicated to genres including gospel, blues, jazz, R&B and hip-hop, plus a 200-seat theater and rotating exhibits.

President and CEO, H. Beecher Hicks III, sat down with The Tennessean in an interview to reflect on the journey from concept to completion.

“We started down this path quite a long time ago with a simple idea: ‘Let’s build a museum and celebrate African American culture,'” he says. “Who knew that ultimately it would cost $60 million and take 20 years to do it?

George Walker IV / The Tennessean

“It has been full of ups and downs,” Hicks says. “I know that a lot of folks along the way, for good reason, had doubts that it would ever come to pass. But thankfully, the board of directors and a wave of staff over the last several years really stuck with it and pushed hard.

Efforts were further complicated by the global coronavirus outbreak.

“And this construction team has been really working double time even in the midst of this pandemic to move the project forward,” he said. “So it’s exciting. After 22 years, it’s all really finally coming together.”

FIRST LOOK: National Museum of African American Music is opening in Nashville

Origins of NMAAM

The museum's story begins in 1998 — more than a decade before Hicks would arrive on the scene. And it began with a question that late civil rights champion and businessman Francis Guess asked himself.

Guess was driving home to Nashville after attending a charity gala in Atlanta, at the home of baseball legend Hank Aaron.

“He was really impressed with the diversity of folks that were there,” Hicks said, recalling the story Guess told him.

“On the drive back from Atlanta, he was thinking, essentially, ‘Why not Nashville? We really ought to have something like that here.’ I don’t think he went home. I think he went directly to the home of his friend T.B. Boyd, and they stood outside in the driveway and talked about what could be.”

By 2001, a task force had been formed, and chartered the Museum of African American Music, Art and Culture (MAAMAC). Beyond music and art, it also aimed to explore sports and civil rights.

But over the next decade, its scope was streamlined — especially once Hicks became the museum’s board chair in 2010.

In 2011, the name changed to the National Museum of African American Music.

“I made the point that the thread that ties all of that together, whether it’s success in sports or the success of civil rights movement and others is song,” Hicks said. “And so I said, ‘Listen, we will make sure that the art and the culture is not lost.”

The National Museum of African American Music resides in the 5th and Broadway development in Nashville, Tenn. Visitors will be able to enjoy the museum when it opens to the public in late January 2021.

George Walker IV / The Tennessean

Why Nashville? Why not?

It’s a question Hicks has heard since he first joined the project: Why is this museum based in Nashville, instead of Atlanta, Chicago, Memphis or Detroit, among other famed hotbeds of Black music?

He has no shortage of answers. The simplest one: “Nashville decided to do it, and nobody else did.”

From its earliest stages, the project was supported and encouraged by the city’s Chamber of Commerce, tourism board and many local leaders.

Then in a development deal for the site of Nashville’s former downtown convention center — the $450 million Fifth + Broadway complex — city officials required the museum be included, ultimately gifting 56,000 square feet of space to NMAAM.

Nashville Mayor David Briley and National Museum of African American Music President and CEO H. Beecher Hicks III shake hands Aug. 29, 2019. Briley and Hicks signed a lease officially granting the museum control over its space in the Fifth + Broadway commercial development.

Nashville Mayor David Briley and National Museum of African American Music President and CEO H. Beecher Hicks III shake hands Aug. 29, 2019. Briley and Hicks signed a lease officially granting the museum control over its space in the Fifth + Broadway commercial development.

In addition, Nashville has its share of Black music history to celebrate, including trailblazers such as the Fisk Jubilee Singers (the group celebrates its 150th anniversary this year) and harmonica great DeFord Bailey, who was the first Black star of the “Grand Ole Opry.”

Nashville is center stage in Tennessee, a state that encompasses blues, R&B, rock and gospel, in addition to country music.

“If we’re going to be Music City — country music’s great, and I enjoy it, but that’s not all that’s here,” Hicks says. “We have the opportunity as a city to capture that brand, and really continue the success of the city.”

SIGN UP: Get more Music City in your inbox with The Pick newsletter

First look at the National Museum of African American Music

A goal ‘to bring us back together’

Last summer, while the Museum was in its final months of construction, the U.S. was in the midst of its biggest moment for civil rights in 50 years. When the massive Teens 4 Equality march made its way through downtown Nashville on June 4, it made a purposeful stop at the museum..

A lot of people are trying to wake up to the Black experience and understand it a little bit better. But also, our country probably couldn’t be more divided. And we need things, like a museum that celebrates music, to try to bring us back together.

H. Beecher Hicks III

“I got several emails earlier in the week. Folks were shutting up their businesses early and putting plywood on the walls,” Hicks recalled. “Well, my response and our staff’s response was to go march with them.”

Hicks and his staff were touched that even though they were still under construction, “the symbolism of the museum was significant enough to draw attention.” Throughout the organization there’s hope that the museum will continue to be a unifying beacon in the years to come.

“A lot of people are trying to wake up to the Black experience and understand it a little bit better,” Hicks said. “But also, our country probably couldn’t be more divided. And we need things, like a museum that celebrates music, to try to bring us back together.”

Blues. Jazz. Gospel. Soul. R&B. Funk. Rap.

Introducing Hallowed Sound: How Black voices from the South made American music what it is today

Illustrations: Brian Gray and Andrea Brunty, USA TODAY Network

The Blues. Jazz. Gospel. Soul. R&B. Funk. Rap. So much of the greatest music ever made was born and raised in the American South. It grew out of the soil in the Mississippi Delta, careened off liquor-soaked bars in New Orleans, and echoed out of juke joints from Alabama to Arkansas. Studios in Memphis and Muscle Shoals spread the sounds, and Motown polished them for the masses. As OutKast’s Andre 3000 would eventually and eloquently declare — a full century after Tennessee’s Fisk Jubilee Singers began exporting American Black music across oceans — “The South got something to say.”

Last month, the National Museum of African American Music opened its doors in Nashville, to honor and preserve the legacy of Black artists. Some of that history has been forgotten. Black-owned and patronized clubs where Duke Ellington, Billie Holliday, Muddy Waters, Otis Redding, Aretha Franklin, Sam Cooke, Marvin Gaye and hundreds of other brilliant artists nurtured their careers have been closed, gentrified, bulldozed over in the name of progress.

The stories that follow — reported and told by more than a dozen USA TODAY Network journalists around the country — are not an exhaustive or definitive picture of the indelible contributions of Black musical artists to American culture. We hope rather, in the spirit of Black History Month, to illuminate a few stories, a few places and some of the people who helped make music what it is today.

The roaring nights that shaped American music

An American musical institution

In 1871, Fisk Jubilee Singers introduced the world to “slave songs” or “negro spirituals” — music Black Americans made for themselves. A century and a half later, the group still endures.

Blues shapes music for generations

Mississippi may be the birthplace of the blues, but as it grows and evolves, its impact is becoming more global.

- Got the blues? Check out these 25 essential Mississippi Delta blues songs

Cultures, sounds mix in New Orleans to form jazz

Jazz was born in New Orleans. The music still echoes through the city, where young players continue to shape the century-old genre.

Wilson Pickett makes his mark on soul music

The Alabama-born, Detroit-bred R&B singer cut a series of classic hits at Stax Records in Memphis and FAME Recording in Muscle Shoals. The studios became beacons for artists seeking the signature sound.

- Stax Records: 5 essential recordings

- Muscle Shoals: 5 quintessential songs

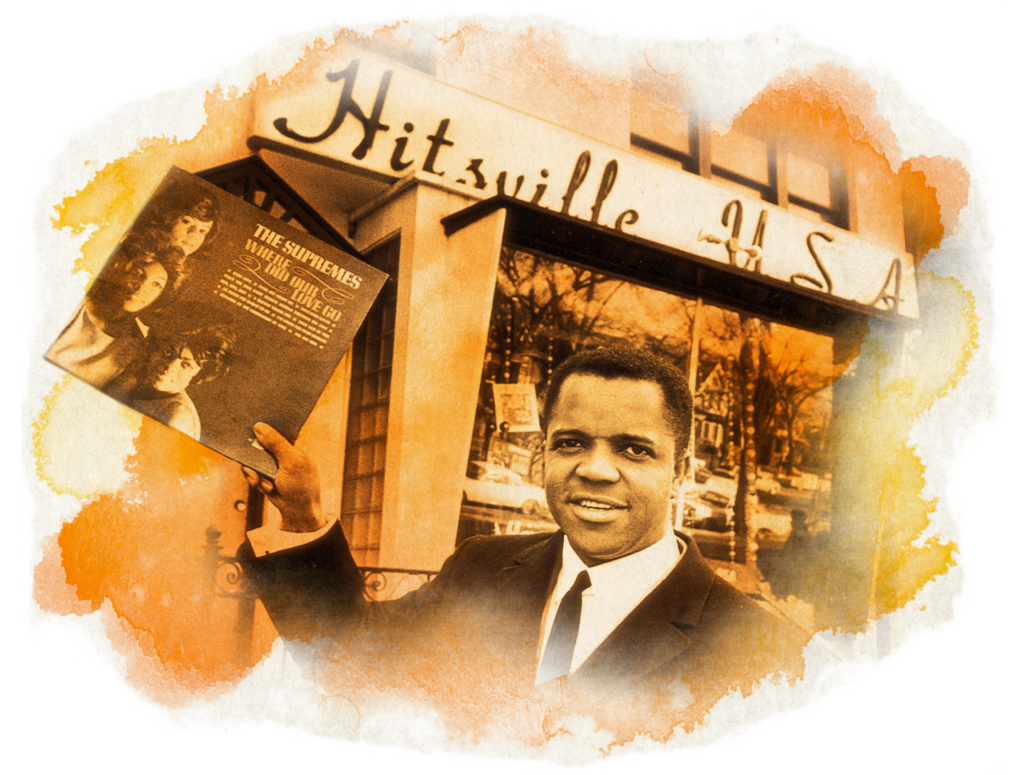

Migration to Motown

Soulful sounds from the South were polished for the masses in Motown. It wasn’t a fluke that Motown Records took flight in Detroit, part of a surge of creative energy that transformed the city into one of the world’s music capitals.

- The ultimate Motown playlist: The 50 greatest hits from the Detroit era

Inside the rise of Atlanta hip-hop

As rappers on the East and West coasts battled for superiority in the 1990s, a new wave of hip-hop came out of Atlanta.

- “The South got something to say”: 30 songs that put Atlanta hip-hop on the map

Black artists in country

Black artists have shaped country music for nearly a century, from DeFord Bailey setting the world “on fire” with his harmonica to Charley Pride’s 29 No. 1 songs to Mickey Guyton’s vital Grammy-nominated 2020 single “Black Like Me.”

Black music moved the movement

From the days of slavery through the Civil Rights Era to the BLM movement, Black music has emboldened American protests with songs so intertwined with events that they’ve become part of the country’s history themselves.

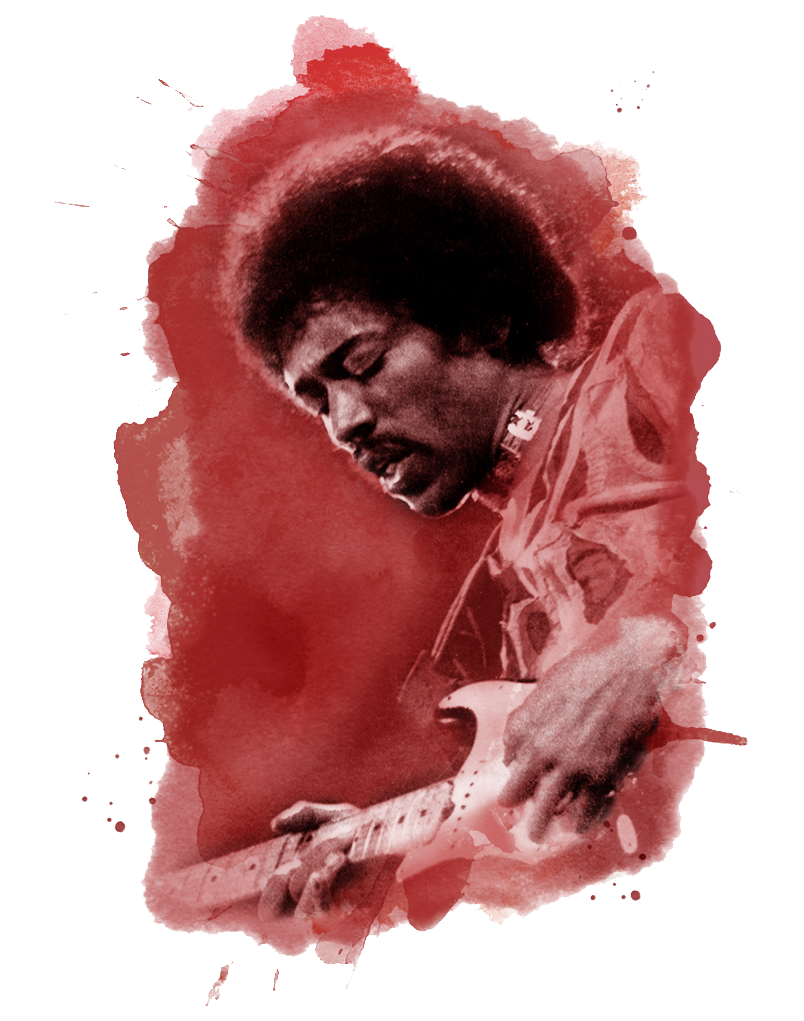

Jimi Hendrix and Jefferson Street

Even as future legends like Little Richard and Jimi Hendrix cut their teeth on the stages along Jefferson Street, Nashville’s R&B scene was all but invisible to the rest of Music City.